The committee also reported on its findings regarding the health problems that can occur in women with implants. These included

The most serious of these problems are 'local' complications, meaning those that occur in or near the implant. Although generally not life threatening, such complications can cause discomfort and, in some cases, pose considerable risk. The IOM committee believes these local complications—which occur often and may themselves prompt additional medical procedures, including operations—are the primary safety issue with silicone breast implants. The committee also recognizes that many of the reports reviewed in conducting this study were based on silicone-gel implants that were largely replaced by saline-filled implants in the early 1990s, and the risk of local complications is likely even lower with saline-filled implants.

Finally, although breast surgery has a low risk of death, many complications can occur when implants are removed, revised, or replaced.

Some of the problems the committee found follow.

Frequent Complications Mean Frequent Procedures

Frequent local complications include the rupture of silicone-gel-filled implants, the deflation of saline-filled implants, severe contracture of fibrous tissue around the implant, infections, hematoma (a pooling of clotted blood), pain, and implant displacement. The end result of these problems may be more surgery or other medical interventions.

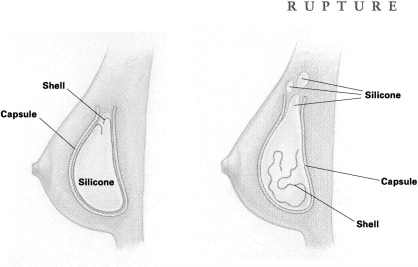

RUPTURE Rupture occurs when silicone gel escapes the implant shell. Such a rupture may be caused by tiny flaws in the shell or by inadvertent needle pricks while the incision is being stitched up. Ruptures can also happen after a needle insertion (a biopsy, for example) or when the breast is severely squeezed or compressed either during procedures to break up fibrous tissue (capsular contracture) around the implant, or because of trauma caused by an automobile accident or even, some say, a too-tight hug. The implant shell may also weaken with time; in fact, this can be expected with older models.

With the rupture of a silicone-gel implant, the gel and fluid can sometimes escape into other tissues and even form an unwanted lump somewhere else on the body, such as the arm, armpit, or chest area. Often, however, the space between the fibrous capsule (which forms around all implant shells) and the implant can actually contain the gel, keeping it from spreading into surrounding tissue, so that the rupture goes unnoticed. This type of rupture is called 'intracapsular.'

One of the questions the IOM committee hopes will be explored is whether screening measures should be undertaken to find these 'hidden' ruptures or whether diagnosis is necessary in women who have no symptoms (e.g., pain or leakage).

When both the implant shell and the capsule of a gel implant rupture or leak, the result is an 'extracapsular' rupture that allows silicone to spill out or leak into body tissues. Most surgeons believe this condition should be corrected.

Surgery for extracapsular rupture consists of removal of the implant (explantation) as well as the capsule surrounding the implant (capsulectomy). These operations will require anesthesia, incisions, and stitches. And, of course, the surgical procedure may include a new implant as well.

The frequency of implant rupture is unknown. The IOM committee found studies reporting that the frequency of gel-filled implant ruptures varied from 0.3 to 77% of implanted women. The extreme variability of these percentages is due to the type and model of the implants, their length of implantation, the types of groups of women studied, and many other factors. Other investigators found no ruptures in late-model ('third-generation') gel implants, but more time is needed to observe these implants. Some reasons for the confusing statistics about ruptures are (1) ruptures are not always detected, (2) the composition of implants has undergone many changes over the years, and (3) the time interval varies and is not long enough to pick up late ruptures. Because of such conflicting information, the committee recommends further studies.

Further, the IOM committee concluded that it is unclear whether implants in current use will need replacement in 10 or 15 years, as some older models did, or will last longer.

DEFLATION It is usually very easy to spot a saline implant that has ruptured—within 2 or 3 days the harmless saltwater solution spills out into the surrounding tissue and the implant collapses, or deflates. Only occasionally does a 'slow leak' (partial deflation) take from 1 to 2 years to become noticeable.

Although early saline implant models had frequent deflations, later models are less likely to do so—a 5 to 10% frequency after 10 years, according to one study. Ruptures, leaks, and deflations may be more common in gel-filled implants than in current saline-filled models, although one team of investigators showed that only 67% of saline implants were still in place at the end of 10 years, causing the researchers to comment that their study 'confirms the obvious: Inflatable breast implants deflate with time.'

The IOM committee concluded that deflation of modern first-year saline implants might run from 1 to 3% and that this percentage would rise steadily with time. The report strongly recommends that more studies be conducted to answer questions about today's implant rupture and deflation rates.

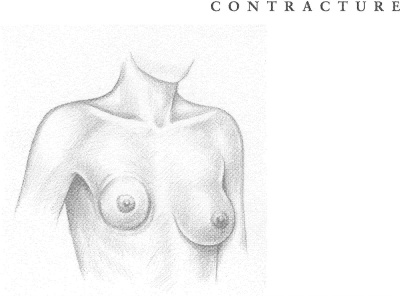

CAPSULAR CONTRACTURE The human body considers a breast implant—or any implant—to be a foreign agent and forms a protective capsule of fibrous tissue around the intruder, resembling the immature scar formed after a severe burn. This buildup of tissue is called a capsular contracture. If severe, it can cause painful and disfiguring squeezing as well as distortion of both the implant and the overlying tissue. The ensuing complications can be serious, including additional medical procedures to break down the overgrowth of protective tissue, or to remove it, or even to replace the implant itself. Additional surgery comes with its own risks, including infection, possible ruptures, and the hazards of anesthesia.

Some of these medical procedures—particularly 'closed capsulotomy,' where strong pressure is applied to the outside of the breast to help break up the fibrous capsule—are performed repeatedly on the same women. Problems with capsular contracture made up 28% of secondary procedures done on women with breast augmentation and 14% of those with reconstruction. A recent study showed that contracture was the reason for 73% of implant removals.

The severity of contracture is often measured using the Baker Classification, which has four categories:

View in own window

| Class I | The augmented breast is as soft as a nonaugmented one. |

| Class II | The breast is less soft and the implant can be palpated (felt) but is not visible. |

| Class III | The breast is firmer and the implant can be palpated easily and can be seen (or a distortion can be seen). |

| Class IV | The breast is firm, hard, tender, painful, and cold. Distortion is marked. |

Most surgeons consider the first two classes satisfactory but not the last two. Women, however, have often tolerated Class III and IV contractures either by not seeking any medical help or by indicating, when asked, that they are satisfied with their implants. A 1990 study reported that 85% of women appeared satisfied with their implants even though 35% had experienced severe contracture.

A 1997 report on 186 implants showed Class III and IV contractures continuing to occur, 'reaching 100% around silicone-gel-filled implants at 25 years.'

Treatments for contracture other than closed capsulotomy include 'open capsulotomy,' in which an incision is made into the body to break up the capsule, and a 'capsulectomy' or surgical removal of the capsule itself. This operation may also involve removal and replacement of the implant as well as loss of breast tissue. Replacement and capsulectomy also involve as much as an hour or more of operating time. The IOM committee reports an excess use of some procedures, particularly the closed capsulotomy, in treating contracture. Repeated capsulotomy, open or closed, has progressively less chance of success. Contracture with its treatment is an important and incompletely resolved issue in breast surgery. It is likely that contracture is a progressive phenomenon, slowly increasing with time.

Scientists and doctors do not know for sure why severe contracture happens. Some have suggested that trauma to the breast during the implant surgery itself or at another time may bring about thickening and constriction of the capsule. The silicone used in implants has also been named as a culprit in contracture capsules formed around gel implants. The IOM committee noted that most studies agree that baseline levels of silicon are found in all normal breast and other tissue. Definite proof of a relationship between the presence of silicone in the tissue and contracture is lacking, but silicone fluid injected directly into the breasts (an early and improper practice) does cause fibrosis, or hardening of tissue.

Although definitive studies are limited, evidence suggests that saline-filled implants have a reduced rate of contracture compared to implants filled with silicone. Fewer cases of severe contracture are also reported in studies of textured-surface implants compared to those with smooth surfaces. Both patients and doctors in a 1997 study preferred the textured surface.

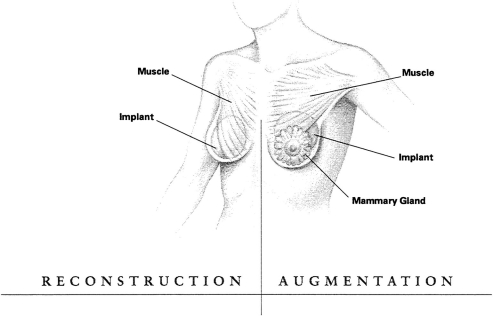

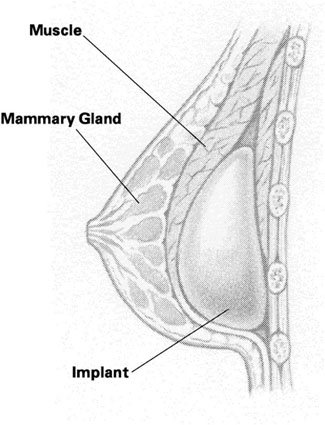

In one clinical study, women undergoing immediate reconstruction after mastectomy also showed fewer cases of contracture than did women having later reconstruction. And, after 5 years, contracture among reconstructed women in the study was less frequent than that among augmented women. However, the women with reconstruction had a much higher proportion of textured-surface implants and implants placed behind the chest muscles than did the women with augmentation. This probably explains this unexpected result and suggests how effective texturing and placement can be in reducing contracture.

Placement of the implant behind the chest muscles seems to lower the chance of contracture. One study demonstrated that the rate of contracture is 30% with submammary implants versus 10% with submuscular implants. The lower incidence of severe contracture with submuscular implant placement is important. The IOM committee believes patients and surgeons should consider this factor when discussing implant surgery options.

Despite the possibility of contracture, some plastic surgeons still put the implant just beneath the skin or breast or glands in 32% of augmentation implants, probably because the procedure can have a better cosmetic effect and cause less long-term pain than the submuscular procedure.

The use of steroids to reduce capsular contracture is not recommended. Steroids placed inside saline implants may carry other health risks and are not approved for use by the FDA. In addition, steroids may weaken the implant shell. The IOM committee recommends that any use of steroids should be postponed until carefully designed studies can be conducted to determine the risks and benefits of such use.

INFECTION Infection can cause serious complications. Sometimes an infection can develop in the area where the surgery was performed, requiring medical treatment, additional surgery, and possibly removal or replacement of the implant.

Most local infections—those due to bacteria such as staph, for example—may be treated with antibiotics. These infections are reported most often in women who have had reconstruction, particularly immediate reconstruction after mastectomy. Sometimes infection can lodge in the expander used in some reconstructions. The ducts of breasts also collect some normal bacterial inhabitants of the skin area, and occasionally these may cause infection.

Infection may even contribute to the development of severe capsular contracture. The very medical procedures used to correct the condition may expose the area to more bacteria. One of the problems is that slightly abnormal and not easily detected infectious conditions can exist in a 'slime' layer around the implant where the infectious agents are protected from the effects of antibiotics. According to some studies, these 'subclinical' infections may also contribute to such symptoms as fatigue, muscle or joint pain, and diarrhea.

In one study of various implant devices, 93% of the women who reported pain also had an infection. When patients were given antibiotics (usually for staph) and implant devices were replaced by sterile models, 90% of the new implants were reported to be pain free.

The evidence that the presence of bacteria around an implant might contribute to contracture is not conclusive, but certainly suggestive.

HEMATOMA Sometimes blood or tissue fluid collects around an implant, causing pain, infection, or other complications. In a small number of cases, repeat operations have been necessary to correct the problem. Plastic surgeons often use drains after implant surgery to manage bleeding and the collection of blood (hematoma) or fluid around implants, and some surgeons claim such drains help prevent contracture.

Hematomas may occur, rarely, many years after the implant operation in association with contracture, perhaps because a stiff capsule has developed tiny fractures. The committee concluded that there is insufficient evidence pointing to more frequent contractures and subsequent complications around hematomas.

PAIN Pain is one of the significant reasons for implant removal and replacement, although few studies dealing with local implant problems have involved information about pain.

Some studies have reported that a majority of women do experience pain after implant surgery, and this pain may be long lasting.

Patients also reported more pain with implants after mastectomies compared with mastectomies alone and with implants placed under the chest muscles instead of under the skin and breast glands.

A questionnaire returned to one study group reported substantial local pain after reconstruction (up to 50%) and up to 38% after augmentation. As with other studies, pain was also more common after submuscular (50%) implants compared to submammary implants (21%), and with saline implants (33%) compared to gel-filled ones (22%).

About 20 to 29% of patients with pain required pain-control medication. Formation of the implant capsule, especially when the implant is under the chest muscles, may cause nerve compression resulting in considerable pain that may require additional treatment.

The committee recognized that pain following surgery is not surprising given the damage that occurs to the nerves to the breast during implantation and reconstructive surgery, which in some cases occurs after injury to the nerves following mastectomy and, in some cases, lymph node surgery.

Pain may also be an indicator of trouble ahead. Sometimes the implant has to be removed, or a capsule forming under the chest muscles may result in more compression and pain and lead to more surgical procedures. Much of the pain with a late onset is caused by capsular contracture, but it can also be indicative of bacterial infections or rupture.